About

Science Fiction, Hidden Messages, and Mystical Birds

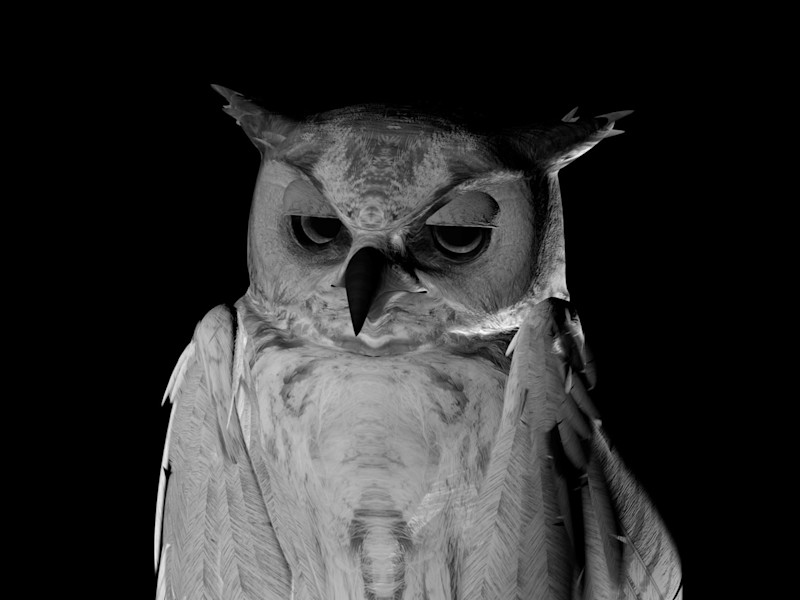

Ann Lislegaard’s works are hybrids creating speculative connections between cinema and architecture, between fictional narratives, between human beings, animals and machines. Her mysterious, digital moving tableaux have bedazzled the international art scene. She has been shown at Moderna Museet and the Gwangju biennale, and has also represented Denmark at the Venice biennale. CFHILL is the first gallery in Sweden to present her work Oracles, Owls… Some Animals Never Sleep (2012–19).

How did these works come about?

— A few years ago, I saw Blade Runner by chance when I turned on the television in a hotel room in Amsterdam. I had seen the film several times before, and I had also read Philip K. Dick’s novel, but this time, I was utterly fascinated by the owl. What I saw made me think about the potential narratives that lie hidden within the silence of objects.

So it made me think:

What if this intriguing and secretive creature were to suddenly receive a voice? What would it say, and how would it say it? This was the initial idea for the piece: giving this animal a voice.

My owl became an Oracle. Just like the Science Fiction genre, it serves as a sort of oracle–a prediction of the future... or, a way to address things that we might otherwise find it difficult to speak about. The oracle is a trickster, both friendly and unfriendly. It seems to make sense but doesn’t, being almost incomprehensible, on the very edge of what we can understand. It speaks in tongues, as if the information passed through its body. It is just as preoccupied with breaking down categories and machines as it is with building them up. Voices, words, sentences, and sounds pass through its robotic body. They are channelled, like a monologue of aphorisms and strangely latent fragments that could be prophecies from the I Ching, or a queer feminist speaking in tongues. You might notice that the soundtrack from the film flows through it as well, in a speeded up and often compressed form.

Naturally, the work isn’t just connected to the film Blade Runner, but also to the novel by Philip K. Dick. When he wrote the book, he often used predictions from the I Ching–the Book of Changes–to guide the narrative and determine which way it should turn or go next. Curiously, Philip K Dick was writing a book called The Owl in Daylight when he died in 1982.

How did you become an artist?

— I think the actual driving force there is the same one that guides my interest in sci-fi. I.e., it is a reflection on the many alternative possibilities inherent to the genre. The fact that you can focus so intensely on just a few projects and explore them in great depth. Many become artists because of somebody in their family, but that’s not what it was like for me. At some point in my life, I realised that I wanted to be an artist. It was as though I’d met an oracle! I remember thinking to myself that there must some other option than to live a normal life in a nuclear family. My experience of sci-fi, and the fact that I grew up north of the Arctic Circle, where we get Northern Lights and no daylight at all for three months, and then no dark during the summer. The fact that there is a place that is entirely parallel to another. Not everything is the same. I also often think about how our lives are so deeply normative. Norms restrain us. A large aspect of being an artist is the way you can work to break down and build up political and social ideologies, including the concepts of language and gender. I did quite well at school. However, I felt that it wasn’t enough. After finishing secondary education I attended a school where I got to work with sculpture, and I thought it was absolutely fantastic. Getting to meet people who shared my interests was fantastic, too.

What do the animals (dog, owl, spider) represent?

— To my mind, they are cyborgs. They’re a kind of hybrid of organism and machine, they’re creatures. It’s reality as well as fiction. They’re animated animals, built up out of something else. They look like animals, but they are really only traces of something else entirely. Just like in our time, when more and more ways of implanting machines in the body have been realised, like automatic insulin level detectors and things like that. Our bodies are turning more and more into hybrids, and aren’t exclusively organic any more. In author Philip K. Dick’s book, there is a character who was born a human, but resembles a machine, and another who was born to a robot, and who needs electricity, but resembles a human being in every other regard, including sexual needs and complex emotional algorithms. It’s a likeness of sorts, but perhaps what one resembles is not what one is. It’s interesting to question our identities; we can see past the visible. The owl in my film is complex. It’s an animal, but it speaks and can be understood. It’s a portal to another insight; an oracle receiving signals. The words don’t convey the full meaning, but they can be decoded based on our own interpretations. Language can accommodate every variety of human experience, but at the same time, reality is more complex than our spoken language, which serves various agendas: grammar, politics.