Pensée Emmanuel Bornstein & Lotte Laserstein Interview by Michael Storåkers

Interview

October 5, 2024

In the exhibition Pensée, works by Emmanuel Bornstein and Lotte Laserstein are brought into a dialog.

In Lotte Laserstein’s painting Abend über Potsdam (Evening over Potsdam) five young people are seated together at a table, each absorbed in their own thoughts. This iconic painting from 1930 conveys an atmosphere of perplexity and uncertainty that can be interpreted as a reflection on the social upheavals at the end of the Weimar Republic.

The encounter between Lotte Laserstein and the artist Emmanuel Bornstein takes place almost 100 years after Abend über Potsdam was painted. Once again, we are experiencing troubled times. Emmanuel Bornstein (EB) and the art historian Anna-Carola Krausse (AK) in conversation with Michael Storåkers (MS), the director of CFHILL in Stockholm.

MS: Emmanuel, I would like to start with Potsdam because I find it so interesting that your exhibition is now taking place where Lotte Laserstein created one of her main works. When did you first see Abend über Potsdam and what did it trigger in you? What references and connections to your own work did you recognize in it?

EB: Three years ago, I visited the renovated Neue Nationalgalerie, which reopened with a new presentation of the permanent collection. The first thing you saw when entering the foyer was Abend über Potsdam. The placement of the painting was peculiar, because you didn’t quite know if you were already in the exhibition or not. It was a kind of transitional space. When I saw this picture I thought: Wow, what is that? The painting touched me immediately, and I had to pause before entering the actual exhibition. I took off my jacket, observed, and immediately fell in love with this picture. I thought it was incredible – the way Laserstein paints is unparalleled. Who paints like that, in 1930? I must confess, at the time I had no idea who Lotte Laserstein was. I went very close to the picture, then back again, closely observing the texture of the paint application. I was fascinated by so many things, by the quality of the painting itself, by the gazes, by the figures, and the motif as a whole. It was exactly what I had been trying to do for years! The title suggested a historical or local reference, but the fascinating thing in this picture is the people, people who are waiting. What were they waiting for, in 1930? Now of course, we know in hindsight what they were contemplating, what they were struggling with. I was totally blown away by this painting. At that time, I had just started painting the Shelter series, where the central motif is people in waiting. In my paintings, there is a palpable danger, but it is not visible. The paintings are seductive because they are so colourful and at first glance, you do not realize that there is an element of threat in them.

MS: How did you and Anna-Carola, the leading expert on Lotte Laserstein and one of the two curators of the aforementioned exhibition at the Moderna Museet, meet and start working together?

EB: Do you want to answer that, Anna?

AK: A Laserstein collector approached me and told me that a young artist, whom he highly respects, wanted to do a dual exhibition with his own work and Laserstein’s paintings. The collector asked whether I would consider meeting with him. I must admit, I was initially quite sceptical. Was this someone who wanted to use Laserstein as a teaser for his own exhibition? However, I was also curious. Emmanuel and I met in a café, and we immediately had an incredibly animated conversation; Emmanuel told me about his family background, his artistic approach, his previous works, etc. He was able to plausibly explain what fascinated him about Laserstein’s art and why he was so interested in this combination. Based on the works he showed me on his mobile, I could understand that well. What ultimately convinced me in the end was a visit to his studio where we discussed at length in front of the works. There are so many subtle parallels, but of course also clear differences. It is precisely these differences in the similarity that make this artistic encounter so exciting. To give an example: The large-format compositions of the Shelter series or the Vaterfiguren appear at first glance much louder than Laserstein’s compositions. And yet these colour-intensive paintings also have a quietness, sometimes even a certain melancholy, which can always be found in Laserstein’s works. The portrait series Another Heavenly Day in turn immediately reminds one of Laserstein’s intense en face portraits. In short: it was evident that an interesting artistic dialogue could take place here. Moreover, I thought it was fantastic that the works Lotte Laserstein painted almost 100 years ago still mean something to a contemporary artist today – and Laserstein would surely have been pleased (laughs).

MS: In 1961, Emmanuel’s grandmother, Carmen Bornstein-Siedlecki, was awarded the Legion of Honour for her services in the French Résistance. Her former commander in the Résistance, Jean Gay, ended a letter to her with the words: “Hundreds of thousands of other patriots have died to secure the bread, the spirit, and the flowers in their homes for all little Henri’s and Henriette’s of France and the whole world.” The flowers appear here as a symbol for a place that is primarily to be understood psychologically: the home. Your flower pictures are very complex, also metaphorically charged. Not only does the title Pensée have multiple meanings, but these paintings also deal with memories, family history, and belonging. How does this relate to the works of Lotte Laserstein, who also often turned to the motif of flowers, albeit in a quite different way?

EB: I do not call these paintings flower pictures. I call them Pensée, because for me they are thoughts, which means “pensées” in French. Pensée is also the name of a flower [in English: pansy], and then of course they are also like a memory, like those I might have had of my grandmother. When the Pensée series was first exhibited at the Galerie Crone in Vienna, it stood out because it was hung next to the Shelter works, which are rather narrative, with clearly outlined figures whose gazes form the centre of the picture. In the Pensée pictures, however, the contour explodes and there are only colours. It looks as if the motif of the bouquet of flowers is in a state of dissolution. Suddenly, the lines disappear, and you have these colours that directly interact with the nervous system.

I would like to come back to that letter from Jean Gay that you mentioned. Carmen, my grandmother, fought as an active member of the Résistance against the advance of the Nazis in France and was arrested by the Gestapo in 1944. At the age of nineteen, she was deported to Auschwitz, where she withstood torture and survived. In 1946, she gave birth to my father. She died early, not least because of the consequences of imprisonment, when my father was nineteen years old. He suffered greatly from the loss of his mother, but also from her inability to tell him about her traumatic experiences. The fate of my grand- mother plays a central role in my life and my art.

I never had the opportunity to meet my grandmother, but I inherited the family trauma. In 2017, my father discovered official documents with the help of Serge and Beate Klarsfeld, that shed new light on his mother’s struggle. After the end of the war, she was in a Kafkaesque conflict with the French authorities. She fought for recognition of the fact that her deportation to Auschwitz was a result of her political activities, and not based on racial rea- sons (she was Jewish). After twenty years, she finally succeeded and received the said honour in 1964. Unfortunately, she died just two years later.

I dealt, artistically, with this story in a series titled Three Letters, and shortly thereafter I started working on the Shelter series. When Jean Gay talks about the little Henri and Henriette in his letter, he also meant my fat- her. My father was named Henri, Jean Gay was his god- father. While I was working on the Shelter series, I told myself: I will allow myself to paint flowers. Will they just be flowers – or will something else come out of it? I considered: What is a Shelter? It’s a space that protects you from something. Does a shelter with flowers become a home? Where do we draw the line? Can a shelter become a home if you have been taken away from your home? I created this dialogue between the Shelter and the Pensée series with Jean Gay’s letter in mind. I painted the flower motif over and over again, until it became very free and loose. That’s when I realized that these Pensées are not just flowers. They stand for something else. That was exciting.

When I later searched for works by Lotte Laserstein for the exhibition with Anna-Carola, I discovered Lotte’s flower pictures and began to see all these connections: Laserstein’s flower still lifes have about the same format as my Pensée. I also realized that Laserstein had painted them exclusively in Sweden, not in Germany. Stockholm became her new home, her “shelter,” since she had to flee from Germany. Ultimately, perhaps her flowers can also be seen as a pensée? In Germany in 1930, she painted her masterpiece Abend über Potsdam, demonstrating her entire artistic skill, and in Sweden, these fragile little “flower thoughts” were created. To be honest, this thought connects me again to my grandmother. I hope that the exhibition will make it clear that the flowers were not just a stylistic exercise for her, but a way to make another country her home.

AK: I like this idea of “home.” For Laserstein, home, if you will, was painting. When she painted, she was with herself, even in foreign places. The flower paintings were mostly created when there was nothing else to offer, when there were no portraits to paint, no models available, when it was too cold for plein-air painting – or simply for relaxation. The flowers were not a great challenge for her, but they were like her artistic food, something very necessary. She simply had to paint something.

EB: Funny, Anna, that you just use the word “food”. And there we are again at the “bread, the spirit, and the flowers...” of Jean Gay. You might call it a ritual, a little work that doesn’t cost more than two hours of your time, yet it bears significance. There is a beauty, and something very poetic in these non-challenging pictures. As a painter, you cannot only create demanding, large, narrative works.

MS: Emmanuel, you once said, “painting becomes active as a medium: it is not only used to depict but becomes productively effective. The investigation does not proceed via, but through the paint”. I think of your use of the colour yellow as a structuring element. Laserstein’s use of colour is also remarkable. At first glance, your palette is quite different. Her tones are rather subdued, ochre, and earthy. Would you still say that there are similarities in the way colour is used in your respective works, whether metaphorically or structurally? You always start with yellow, right?

EB: Yes. I have been working with cadmium yellow, this toxic colour, for about 20 years now. I started using it at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Then I came to the University of the Arts in Berlin for an exchange program. Here in Germany, the question of evil preoccupied me. Where does all the evil in our world come from? I drew grotesque human processions – and stopped painting in colour completely. Only in black and white. Somehow, I couldn’t use colours anymore. At the same time, I wanted to develop further alongside the contemporary German artists who were painting incredibly colourfully at that time. By imposing this restriction on myself to use only black and white, I could almost try out a new painterly syntax. But it was also a way to paint my nightmare, a kind of dream- like grotesque, which was strongly influenced by Goya, a bit like his etchings, only translated into painting. When I returned to Paris in 2010 for my exam, I suddenly realized that something was missing. Over the next six months, I tried to find a new differentiated approach to colour. It was a disaster! It was really chaotic until the idea came to me - I don’t remember exactly when, but it must have been sometime that year - what if I covered the canvas with this very bright cadmium yellow as the first colour after the priming? Almost as a basis on which I then work with black and white. It was astonishing how the relationship between the black and white on the yel- low ground completely changed. I realized how diverse, but also how ambivalent yellow can be. It can convey a feeling of warmth and security, but it can also become something unpleasant.

MS: Anna-Carola, when we think of Laserstein’s palette, we see rather dark colours. But it has changed a little over time. Can you tell us a bit more about her colours?

AK: Yes, as you say Michael, Laserstein’s palette was rather subdued. She often used earthy tones, brown, ochre, a dark green. It is interesting that she used these colours primarily in the Berlin years, at a time when the metropolis was full of energy and dynamism. It’s almost as though she wanted to create a counterpoint to this hyperactivity with her subdued palette. Her quiet, often statically composed pictures could almost be read as an invitation to pause. However, this colour restraint changes abruptly when she comes to Sweden. Suddenly the colour becomes brighter, fresher, the drawing of the figures becomes lighter, sometimes almost reminiscent of the Swedish painter Carl Larsson. The reasons for this change are quite easy to name: She had to make a living from her art and the Swedish audience found her pictures, which she had been able to save from Germany in exile, to be too gloomy, too heavy, too German. So she adapted and modified her palette – even though subdued colours and darker tones would have been a more accurate expression of her state of mind, given her difficult situation as an emigrant.

MS: In an interview, Emmanuel talks about the “healing function of art” - that one must depict a trauma in order to overcome it. Anna-Carola, could you please shed some light on Laserstein’s “trauma”? Particularly her difficult time in Berlin after 1933, which is already foreshadowed in the Potsdam picture, which eventually led to her having to emigrate. In Sweden, she worked as a commissioned portrait artist, painting representatives of the nobility and the economic, political, and cultural elite. Was this also a way to heal, or was it more a way to survive?

AK: Was this also a way to heal, or was it more a way to survive? That’s a good question, which requires a nuanced answer. I would not consider it an either-or scenario, but rather a combination of the two. She had to paint to earn money, so she primarily worked as a commissioned portrait artist. These commissions were also important in order to stay in the country. Without proof of pending commissions, she would have been sent back to Germany after three months. Painting was a form of survival strategy. At the same time, painting surely also had a “healing” effect. The Nazis had excluded Lotte Laserstein from the art world - one could say they robbed her of her identity as an artist. In Sweden, she was once again perceived as “the painter Laserstein”. The customers – you said it already, Michael, including many well-known personalities of the Swedish society – brought her respect and appreciation. However, the commissioned painting led to a severe crisis after about 10 years, so the “healing” power was of limited duration. Laserstein struggled with herself, believing she had lost her creative power through commissioned painting. To counteract this, she began to paint a series of self-portraits, something she had done surprisingly rarely in Sweden up until that time. As if she had been afraid to look into the mirror. In these self-portraits she expresses her worries and troubles for the first time, and she refers to old Berlin works that now become a model for new compositions. For ex- ample, in 1950 she painted the Self-portrait before Abend über Potsdam, as if to say: Look, this is my past. This is my background.

MS: It is often said that she should have stopped painting in Sweden because the Swedish pictures no longer had the same power as the Berlin works. However, I completely disagree. I am extremely impressed that she maintained a consistently high artistic level throughout her career. Even if there are some portraits that are not as strong, she still had remarkable talent. Would you share this assessment?

AK: Absolutely. She was indeed incredibly talented and technically very skilled. Even if many commissioned paintings are actually quite conventional, one must not forget that there are also numerous works in Laserstein’s Swedish œuvre that have a similar power and intensity as the Berlin pictures. I think this is quite apparent in the exhibition at Moderna Museet, where the Swedish work was presented extensively for the first time.

MS: Emmanuel, personal or literary references play an important role in your work. Are there certain literary references or influences that come into play in the Pensée paintings, and if so, how do these complement or contrast the themes treated by Lotte Laserstein?

EB: The written word, writing in general, whether literary texts, letters, or documents from archives, has always been an important part of my work. Similarly, the titles of my exhibitions often refer to figures from literature. In the Pensée series, however, the influences, as we have seen from the letter by Jean Gay, are rather of a personal nature. The series Another Heavenly Day, on the other hand, goes back to a quote by Samuel Beckett. I have been working on it since 2014 – now ten years ago - and I think there are almost 100 portraits by now. Then there is the Shelter series, the series of Vaterfiguren, the series of Mother Figures, and there is the Vladimir and Estragon series. I always work on series in parallel, because al- though they all have their own rules, they communicate with each other, and colour each other. For example, when I work on the Shelter series, suddenly the portraits from the Another Heavenly Day series might echo some- thing from it. Or when I work on a Pensée, the freedom of the brushstroke directly affects the Shelter picture. Inevitably, there is a constant communication.

I hope that in this exhibition you can experience how the works are interconnected, not just intellectually or aesthetically, but precisely when it comes to the ambivalence we spoke about earlier.

MS: Emmanuel, when did you know that you had to paint?

EB: I think I painted before I knew it. Like all children, I made scribbles and small drawings – and I never stopped. Per- haps this was because I was very shy as a child and had found a way to express myself without having to speak. I come from a theatre family. My father was a director and writer of children’s plays, my mother worked at the National Theatre in Toulouse. I followed them to all the cit- ies where they had engagements, as did the children of the other actors and theatre workers. We were constant- ly encouraged to play together on stage. I hated it! It was terrible. I remember crawling under a table, a dog sitting next to me, and I was drawing and painting amidst this creative chaos. I am very grateful that my parents encouraged me to paint and that I could occupy myself in this way. As a teenager, it was more difficult. When you’re 12 years old and don’t like football or rugby, you’re looked at sideways, as if there is something wrong with you. As a result, I had to hide my creativity. Those were not the happiest years.

MS: When did you stop hiding?

EB: Good question. I think that was after I graduated from high school in Toulouse and realized that I would not be happy trying to be like others. I was different. So I decided to apply to École Boulle, a design school in Paris, be- cause I thought it would be easier to earn a living as a designer. I didn’t even last a semester; it was absolutely not for me. I was very young, about 19, lived in a small apartment and worked to pay the rent. I subsequently called my parents to tell them: That’s it. I want to become an artist. “Then at least study at an art school” they countered. I responded that, to make them happy, I would apply to all the art schools in France. There must have been at least five or six, and I was accepted to all of them.

AK: Your determination reminds me a bit of Lotte Laserstein, who also declared very early – and confidently – that she wanted to be a painter. And who pursued this path, which was still difficult for a woman at the time, with great de- termination.

MS: Let’s talk about your identity, Emmanuel. You come from France, you have a German-Jewish background, and will soon become Swedish... what would you say is your identity?

EB: Yes, I assume all those identities, and several others.

MS: Anna-Carola, in your opinion, how did Lotte Laserstein see herself ? Was the question of identity even relevant to her?

AK: I think it’s very important how one sees oneself, what identity one has. Normally one has several. Let’s start with Laserstein’s national identity. I suspect that she never felt Swedish, although she lived in Sweden for almost 50 years and was a Swedish citizen. We know from her letters that she always felt a bit foreign, that she believed she was excluded from certain artistic circles because she was not born Swedish. She was particularly disappointed (and hurt) by the rejection of Konstnärernas Riksorganisation [the Swedish national association of visual artists], where she had applied for membership in the 1940s. The reasons for this rejection were actually in- comprehensible. It should not have been a matter of quality. Here it would be interesting to do some more re- search, in terms of whether a certain xenophobia or la- tent anti-Semitism might have played a role, and to what extent. This brings us to Laserstein’s “Jewish identity”, which coincidentally is a highly interesting aspect of her biography that needs to be further investigated. As we know, Laserstein was raised Christian and was not aware of her Jewish roots. She belonged to the many people who were labelled Jewish by the racial ideology of the Nazis. By contrast in Sweden, her imposed identity as a Jew was immensely helpful: In the Jewish community, she found new customers and met fellow sufferers, people who had experienced similar things as she had... We mustn’t for- get, it was the Jewish community that arranged the sham marriage that made Laserstein a Swedish citizen and se- cured her right to remain. I have often wondered what it does to a person when being Jewish is first a threat that destroys your existence, and subsequently becomes the thing that saves you. However, the most important point in Laserstein’s self-view, in her self-definition, was surely her identity as an artist. Confidently, she presents her- self in many early self-portraits - and again and again later – placed at the easel. Here she proclaims, “Look here, I am a painter, a woman who will not let her place in the traditionally male-dominated art world be disputed”. That, I believe, was the most important point for her when we talk about identity: to be an artist.

MS: Emmanuel, we have seen that Lotte Laserstein, and you follow quite different artistic approaches, yet there are overlaps in the complexity of the works and in the atmosphere of the pictures. Laserstein mostly worked “from life,” that is, with a model. What about you?

EB: I have never done that. I never work with people. I am more of a Francis Bacon-type. I would never have someone pose for me. I work with archival material, with documents, with all sorts of things to avoid having someone model for me, because in the end the personal relationship with the model always plays a role and affects the work. When I start my series, it is rather a process of intense self-observation. I think as an artist you can either paint themes that are very close to you – your lover, your friends, your children, people, and things from your own private surroundings – or you paint the world, our time, where there are many threats, many wars, things that concern us. My work oscillates between the private and the world.

Gallery

Pensée Emmanuel Bornstein & Lotte Laserstein Interview by Michael Storåkers

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensee X 2024, Oil on canvas, 85 x 65 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée II 2023, Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée III 2023, Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée XIII 2024, Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée XV 2024, Oil on canvas, 85 x 65 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Clinamen VI 2018, Oil on canvas, 200 x 187 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée XIV 2024, Oil on canvas, 85 x 65 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Shelter XIII 2024, Oil on canvas, 150 x 400 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Shelter XII 2024, Oil on canvas, 205 x 261 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée XII 2024, Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Reparation 2020, Oil on canvas, 170 x 130 cm

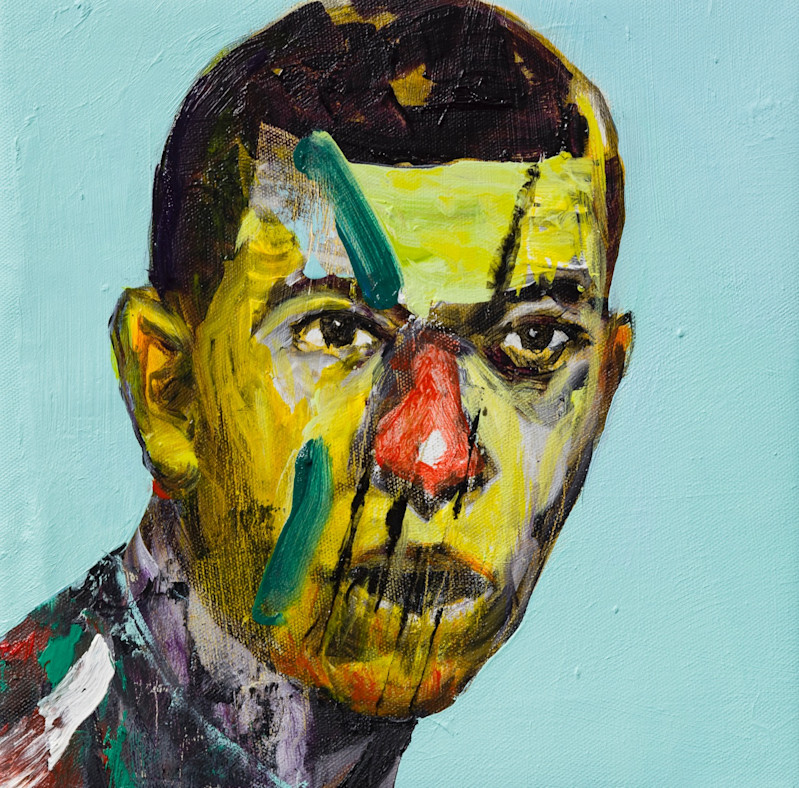

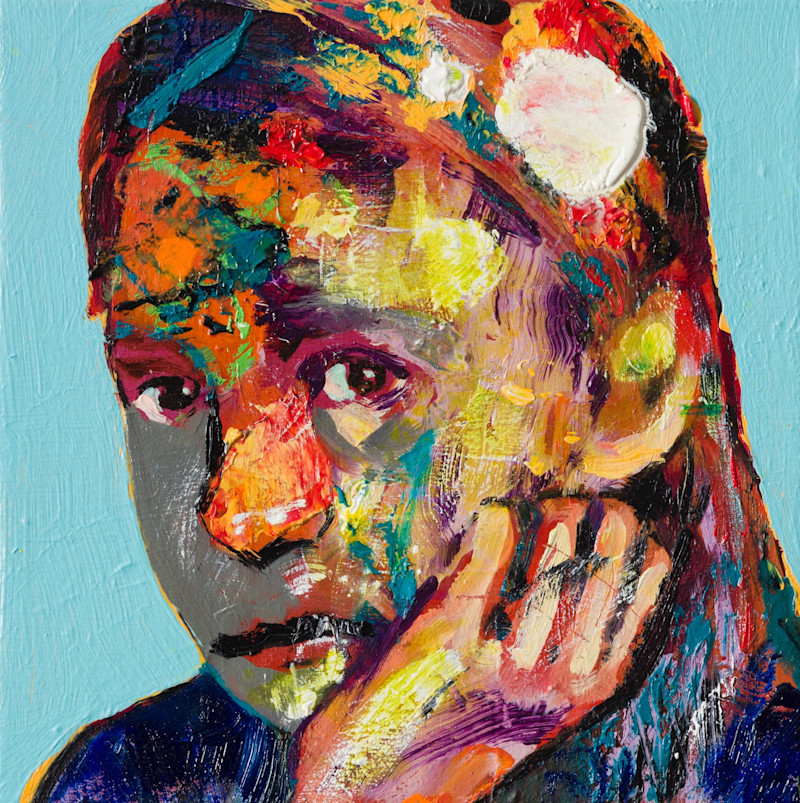

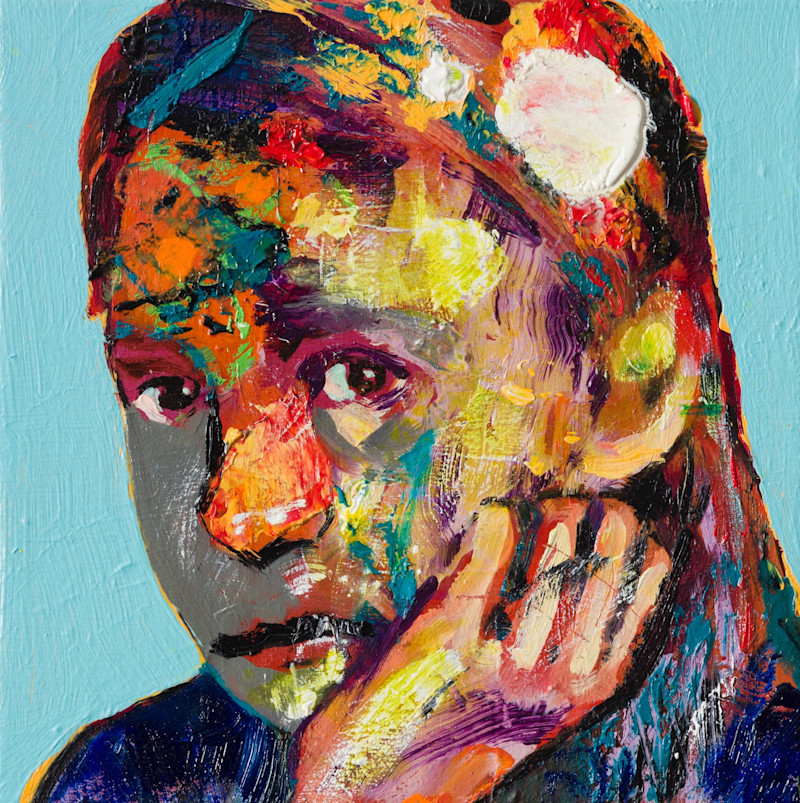

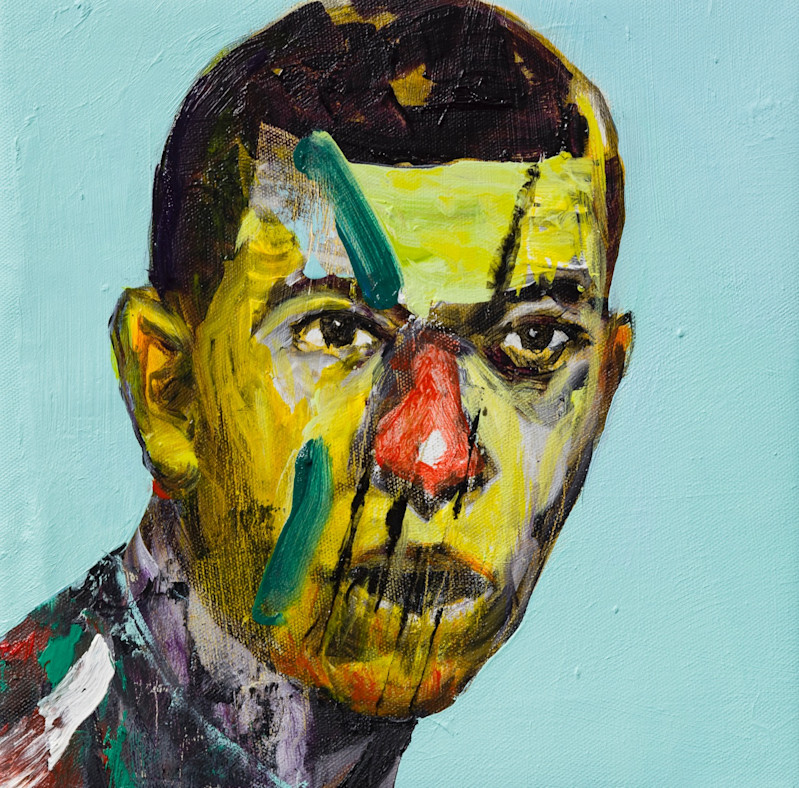

Emmanuel Bornstein Another Heavenly Day XCII 2023, Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée IV 2023, Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Cull V 2022, Oil on canvas, 170 x 130 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée IX 2023, Oil on canvas, 85 x 65 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Shelter XI 2024, Oil on canvas, 200 x 150 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Pensée V 2023, Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

Emmanuel Bornstein Another Heavenly Day XXXIX 2018, Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm

Lotte Laserstein Flicke med blåvitrutig klänning 1930, Oil on paper, 33 x 29 cm

Lotte Laserstein Walter Beyer, drawing 1947, Oil on canvas, 122 x 85 cm

Lotte Laserstein Bondpojke 1920s–1930s, Pastel and gouache on paper, 27 x 20 cm

Lotte Laserstein Dr. med. Annie Spitz 1946, Oil on canvas, 117 x 91 cm